John Karlin – Father of the Modern Keypad

When you pick up a phone to dial, punch in the time on the microwave or pay at the gas pump, you probably don’t need to even look at the keypad, since the numbers line up in the same familiar pattern every time. But that simple keypad you know today evolved through years of careful study on how people dialed phones. Just about everyone takes the telephone button push pad for granted, but one man studied hundreds of options to come up with the best one.

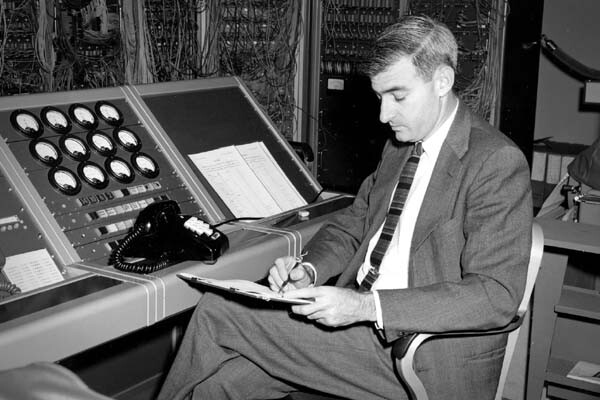

That man, John Karlin, solved the early challenges of phone use. His biggest contribution — the standard dialing keypad — remains the same years after he determined the 12-key arrangement — set up in four rows — was most intuitive. The retired Bell Labs industrial psychologist died almost unknown on January 28 at 94, and the year of his passing coincides with the 50th anniversary of the push-button introduction, on November 18, 1963. But his work lives on every time you pick up a phone and dial.

Karlin wasn’t a typical phone company technician. He not only had a doctorate in mathematical psychology, but studied electrical engineering and played the violin professionally, according to the New York Times. But he made the most contributions with his background in industrial psychology.

“He was the one who introduced the notion that behavioral sciences could answer some questions about telephone design,” said Ed Israelski, an engineer who worked under him.

From 1945 to 1977, Karlin, considered the “father of human-factors engineering,” a field of psychology that studies brain processes and how it affects technology use, worked at Bell Labs. By experimenting with product design, he pioneered in the use of engineering to figure out what people can handle mentally, contributing to not just telephone design, but smartphone innovations in years to come.

Early Years and Research at Bell Labs

Karlin was born in Johannesburg, South Africa and moved to the U.S. during World War 2. He earned his doctorate from the University of Chicago in 1942 and later became a research associate at Harvard, while studying electrical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. While still at Harvard, he did research on psychoacoustics, specifically how jet noises distract crew members from their duties. Like many men of his generation, he started his career working for the U.S. military.

After the war, he joined Bell Labs. As the first research psychologist on the staff, he spent his early years working in telephone acoustics. But phones are more than being able to hear well, so in 1947, he persuaded Bell Labs to create the human-factors engineering department to study how people use phones.

Revolutionizing Phone Design

The earliest telephones didn’t have a dial at all — operators needed to connect calls based on spoken codes. “Pennsylvania 6-5000” wasn’t just the name of a big-band tune, but instead was a telephone number that the Hotel Pennsylvania in New York City continues to use until this day. And later on, those heavy, black phones had rotary dials — numbers placed in a circular, clockwise arrangement. In the decades after WW2, telecoms decided to use of a string of seven numbers for phone codes, but they had problems. People worried how they’d be able to remember all seven of the digits, as well as how long it would take to dial them with a rotary phone.

Rotaries started to give way to push buttons, and social scientists needed to find the best way to arrange the dial. Sure, it seems like a simple matter now, but back then, phone makers wanted to put the buttons in a circle, like the old rotaries, or putting “1-2-3” on the bottom row. Karlin and his team conducted research trials to better understand why people got easily confused by the touch-tone phones. They determined that by putting the buttons in rows, starting with 123 at the top, people could more easily make calls.

He found that the rectangular arrangement follows people’s logical thoughts, and the keypad design he championed became an international standard, not only for phones, but also gas pumps, door locks, vending machines, calculators and cell phones. The arrangement was different from the first model patented by Bell Labs engineer Rudolph Mallina, whose model had buttons arranged in two horizontal rows. That model — as well as designs with buttons in an arc — never took off.

Impact and Legacy

People weren’t initially thrilled by all the changes. Karlin, who was happy to work out of the limelight, found himself the target of scorn, stemming from some of his modern designs. Traditionalists liked exchanges based on spoken codes, and they protested when telecoms phased out those methods. Still, all-digit numbers allowed for more phone numbers as more people got phones, but people missed being able to ask for, say, Pennsylvania 6-5000.

“One day I was at a cocktail party and I saw some people over in the corner,” he said. “They were obviously looking at me and talking about me. Finally, a lady from this group came over and said, ‘Are you the John Karlin who is responsible for all-number dialing?'”

He proudly said he was responsible for the development, and the woman asked him, “How does it feel to be the most hated man in America?” Her comment, though, didn’t foresee the impact his work would have on modern technology. Without his research into push-button dialing, today’s phones, cell phones, microwaves and even television remote controls would look and work much differently — and be much more difficult to use.

One feature from the old dialing systems is still in use today. To keep people happy, Bell Labs left letters on the numbers, even though people didn’t dial with letters anymore — a decision that would have a major impact, years later. When cell phones came out, letters remained on the numbers — and people used them to tap out messages — leading to modern-day texting.

Karlin didn’t know how far his touch-tone psychology would take the industry, but without his early pioneering, the way you make calls and send texts be very different today.